The term “intestate” refers to dying without a will that provides for the disposition of some or all of the decedent’s probate property. This often involves situations where there is no will. But it can also include situations where there is a will, but the will does not dispose of a portion of the decedent’s property. The decedent is said to have died “intestate” as to all or some of his property.

When someone dies without a will, the Texas Estates Code sets out the “who gets what” for their assets. This is the default estate plan for those who do not execute a will. This default plan only applies to probate property, however. Probate property bascially includes everything other than property that passes by trust or by a beneficiary designation, such as in the case of a bank account or life insurance with a named beneficiary on file with the bank or life insurance company.

It is usually clear who gets the decedent’s property when there is a will that disposes of all of the decedent’s probate property. But what happens when there is no will? Who has an interest in the estate? As noted above, Texas law provides the answer. Instead of describing the distribution using words, we’ll borrow the charts provided by the Harris County Probate Court # 1.

This first chart depicts what happens when a married person who had children dies intestate:

If you study the chart, you will see that it divides property into the decedent’s separate property and community property. These are designated by “A” and “B,” respectively, in the chart.

To determine who gets the decedent’s property, you consider A + B.

We’ll explain what community and separate property are later in this guide. For now, suffice it to say that separate property is all property the decedent acquired prior to marriage and property he or she inherited or received as a gift during marriage. All property acquired while married is community property.

You will also note in studying the chart that there are two “B’s.” The second “B” applies when there is a mixed family with children from a prior marriage. In this case, the default estate plan set out in the estates code makes a provision of assets available for the surviving children, instead of giving all property to the surviving spouse. This is intended to protect the children. If this provision was not included, then when the second spouse dies, all of the assets would have passed to the second spouse and would pass according to their will only to their children or descendants. This would effectively cut out the first to die spouse’s children from any inheritance. So when there are children from a second marriage, you use the second “B” in the chart above.

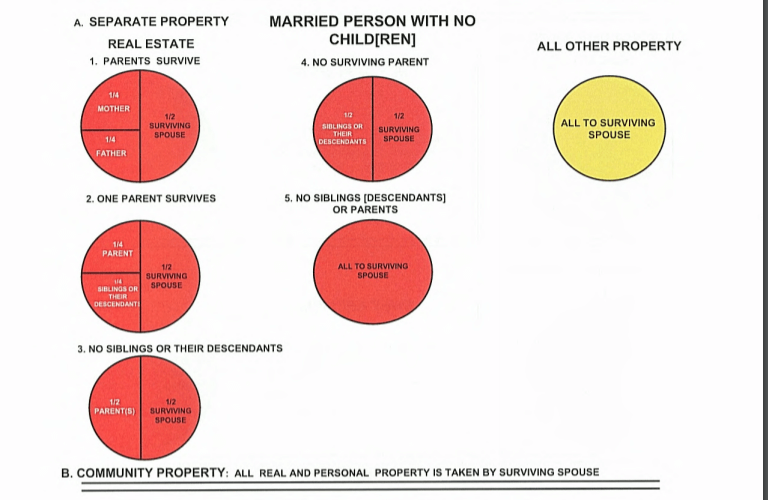

The second chart provided by the probate court depicts what happens when a married or widowed person who did not have children dies intestate:

Like the prior chart, you have to identify the decedent’s community and separate property–“A” and “B” in the chart–to determine what happens to the property.

You will see that the “B” is community property. This passes all to the surviving spouse. The “A” on the other hand passes to the first to die spouse’s parents or descendants. This is best understood by considering short term marriages. Consider an example when a couple gets married and one of the spouse’s dies after a short period of time. The first spouse to die may have accumulated significant assets that would otherwise pass to the new spouse, even though they may not have contributed to the accumulation of those assets.

This third chart depicts what happens when a single or widowed person dies intestate:

This chart is divided into those who die with and without children. There is no “B” for community property in this instance given that there is no marriage. The “A” for separate property passes to the decedent’s parents, or descendants.

Having determined who has an interest in the decedent’s estate, we can now think about the steps for probating the estate. The steps are similar to probating a will (discussed previously), but the process will also require a heirship proceeding and the appointment of an attorney ad litem.

The probate application is similar to the application filed when there is a will. This was covered earlier in this guide. There are some differences, however. These differences involve naming the family members and heirs in the application, to establish that the family history and entitlement to distributions therefrom.

The heirship proceeding is a separate court hearing that a person seeking to be appointed as the personal representative initiates. The purposes of the proceeding is to prove to the probate court who has an interest in the estate. The proceeding starts by filing an Application to Determine Heirship. While it is a separate court proceeding, it is typically handled as part of the probate application. So for most, they do not even realize that there is a separate process–as it is often included in one combined application and one combined court hearing.

The court hearing for the heirship proceeding will include questions by your probate attorney to the person who is seeking to be appointed and two witnesses who were familiar with the decedent and his family and living circumstances. These parties will also be questioned by the attorney ad litem–which is the attorney appointed by the court.

The attorney ad litem is an attorney appointed by the probate court to conduct an investigation to locate missing heirs. This is a requirement before the court will appoint a personal representative. As such, in most cases, the attorney ad litem is appointed on request of the person seeking to be appointed. The applicant starts this process by filing a Motion to Appoint an Attorney Ad Litem and having the probate court enter an order appointing the attorney. This is typically filed along with the probate application and the heirship application.

Before the heirship proceeding can be scheduled with the probate court, the attorney ad litem will conduct his or her investigation. This will typically include reviewing the probate application and heirship application and contacting your attorney to obtain the names and contact information for the witnesses. Then the attorney ad litem will contact the witnesses to get comfortable with their qualification to serve as witnesses, their knowledge of the decedent’s family relationships and circumstances, and whether the information in the applications appears correct.

It should be noted that the decedent’s estate bears the cost of paying for the attorney ad litem. This fee can vary from one court to the next and can be more if more work is required. By way of example, currently, the minimum fee is around $800 in Harris County at the time of this wring. This is usually paid after the heirship proceeding is completed.

Once the application and heirship hearings are done, the next step is for the applicant to take an oath and pick up their letters of administration. These can be obtained from the county clerk’s office.

Letters of administration are issued when there is no will and letters testamentary are issued when there was a will. For convenience, we’ll use the term “letters testamentary” to refer to both documents as they are very similar. This brings us to our next topic. Click here to continue reading. >>>>

Do you need help with a probate matter in Texas? We are experienced probate attorneys who represent clients with sensitive probate matters. If so, please give us a call at 800-521-0230 or use the contact form below to see how we can help.

We can help with your probate matter.